Landscape vs Landscape, Happy

Jean Metzinger’s Landscape (1912–14) hangs in the main room of Cubism at the Museum of Modern Art, which is fitting given the artist being a salon Cubist. The painting, likely painted somewhere in the French countryside given the artist’s life was spent there, shows the promised landscape, though the exact contents of the landscape are not clear. Trees dot the landscape in red, green, and blue. A red parallelogram of a field at the center draws attention, seemingly glinting under an unclear light source on its left. Houses in the lower left, with flat brick patterns and birdhouse constructions, alternate between primary colors at random. While the concept of the landscape is clear, its origins are impossible to trace, shrouded under bright color, patterns, and bizarre geometries. These are classic Cubist constructions with the saturation slider turned all the way. The color is eye-catching, but veers cartoonish or oversimplifying, landing to my eyes a century later basic for the movement. The placement among many other Cubists lets viewers judge it as one entry in the lineage.

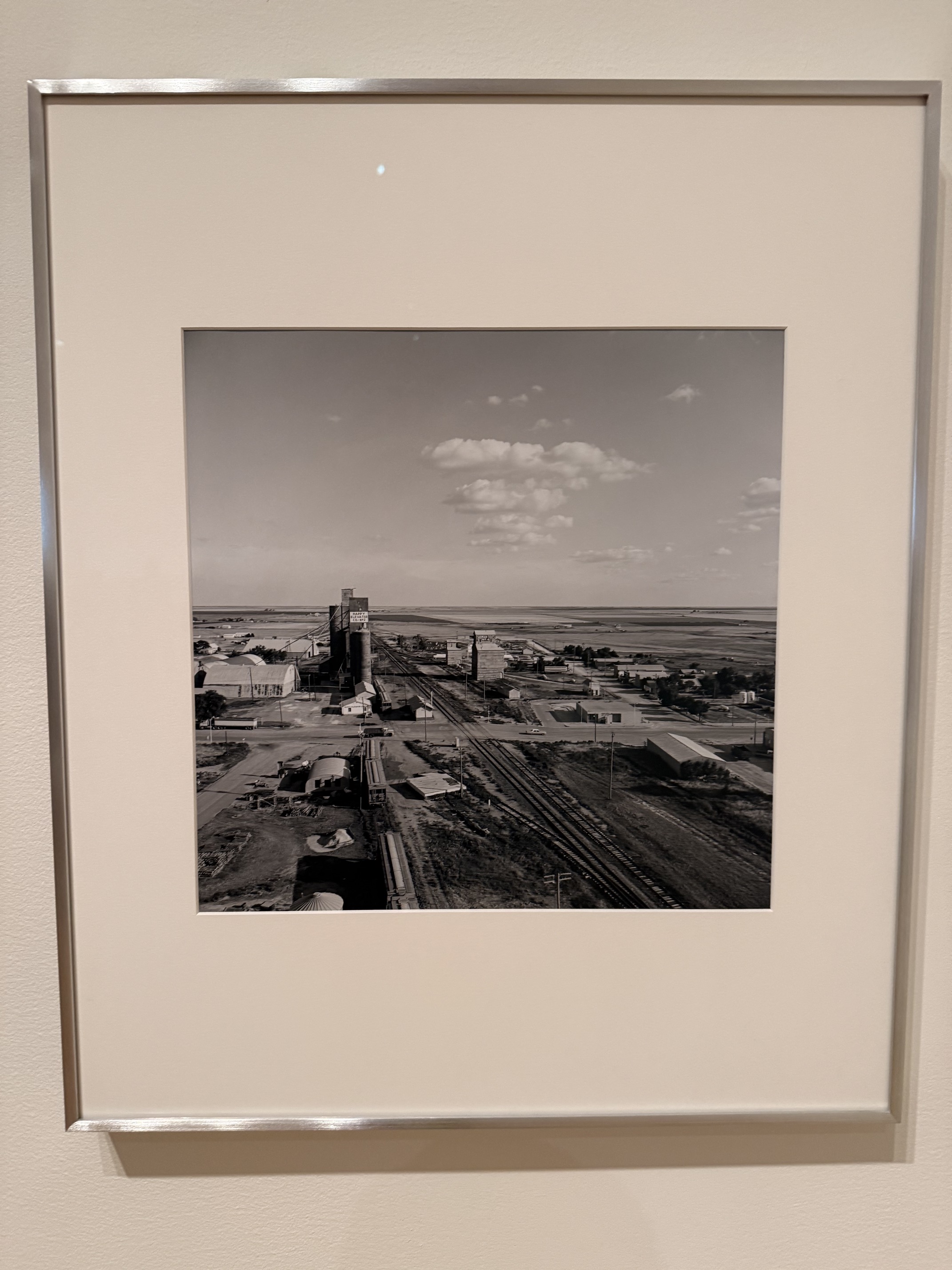

American photographer Frank Gohlke, in 1975, captured Landscape from the Grain Elevator, Happy, Texas. This gelatin silver print, in black and white, shows the titular grain elevator on a vast expanse of landscape, a diagonal railroad crossing a horizontal road across the center of a town more the size of a village. Small houses in the background, with light industrial operations between, surround the towering grain elevator complex. Bright sunlight beats down onto the plain under a few clouds. With the village’s tiny population, there are no visible humans, though two trucks on the road imply drivers. The photograph evokes a long history of 20th century American landscape photography, notably Ansel Adams, in similar content, scale, and medium, with its flat, split composition and stark greyscale. I was enthralled by its glorification of the grain elevator over every other building; the name Happy corresponding with/flying over such a minimal town scene. The photograph is placed in the museum near a Charles Sheeler 1930 painting of a factory in Michigan and a 1948 photograph of a grain elevator by John Szarkowski that is more dramatic, altered, and geometric than landscape.

Today, the grain elevator in Happy, Texas is a Superfund site, a designation of toxic waste contamination by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency begun in 1980. In 1962, a decade before the photograph was taken, a fire broke out at the grain elevator, and firefighters sprayed foams containing a slew of toxic chemicals, notably carbon tetrachloride. These chemicals seeped into local groundwater, in a village of only a few hundred people and little infrastructure. As of the latest documentation from 2024, EPA has not yet built the equipment to begin cleaning up the groundwater.

This timeline positions the photograph in 1975 as after the groundwater was poisoned, and after the facility was rebuilt, but before the Superfund program was created and decades before real environmental cleanup would begin. It crystallizes a moment in time that looks optimistic, with the facility at the center of the town’s economy and geography, flying a high flag announcing the abundance of grain to the surrounding plains of the Harmon-Toles elevator labeled literally “Happy.” How happy this village was is left for us as historians to contemplate; the fire is invisible, as is the pollution underneath that has deeply affected the health of residents. The tone of the photographer himself is unclear. While photography is often assumed neutral or fully representative, this scene shows only an above-ground half of a fuller scene with a more complex story. Today, one of the foremost art institutions in the world proudly displays this half-moment, and spends whatever money necessary to conserve the photograph and keep that moment preserved. Yet in the national government, and the local staffing, preserving the place itself is far secondary to the photograph and the moment; the decades have provided no rush to begin cleanup. How many other moments do we conserve and prize over the people and places they come from?

While lacking any details clear enough to even locate the town, much less trace its environmental history, Metzinger’s Landscape similarly preserves a vision far exceeding the place. Metzinger makes his curation and selected elevation of the natural subjects more obvious—viewers know elements are left out and others exaggerated—and attracts more attention in the gallery with the bright color palette and lighting effects and tucked-in, cute bounds of the composition. Viewers can wonder about the place, and the complex interactions of the industrial with it; I mistook the smokestack in the front left belching large circles of yellow smoke as additional trees over my entire duration in the gallery. The masking of the industrial as natural appears a mere aesthetic exercise for Metzinger, given the painting over a century ago and the work of other Cubists, though it’s possible political commentary is embedded. How climate change from its smokestacks affects Landscape’s origin, we may never know precisely. Now, bringing the two works together in comparison, the Cubist geometries of rectangular trees and round landscape features evoke the circular city hall and rectangular barns in Happy, converting the natural French features into the grid-planned Texan city. Whose representation of the small town is further from the truth gets lost; the abstractions of industrial over natural, artistic over physical, and perceivable versus underground lost without archive.