My Egypt

Charles Demuth painted My Egypt, now hanging in the Whitney Museum of American Art, in 1927 (Whitney). Living most of his life (1883–1935) in Lancaster, PA, he chose a subject close to home, one crucial to the town’s skyline and economy, a grain elevator in the center of the city run by John W. Eshelman & Sons. Painted looking up from a low vantage point, gleaming in the sunlight, “the most striking feature of the painting is the monumentality of the central structure” (Marling 33).

While Demuth used oil paint, and for many other paintings, Demuth is also known for his watercolor sketches. Accompanying a 1950 exhibition of Demuth’s artwork at the Museum of Modern Art, curator Andrew Carnduff Ritchie notes in his monograph that Demuth’s “architectural subjects demanded a larger compass than the watercolor paper provided and a more substantial medium” (Ritchie 7). While early scholarship on Demuth including Ritchie (1950) and scholar Karal Ann Marling’s (1980) do not articulate it, though mention his curation of exhibitions in Provincetown (Ritchie 14), the Demuth Museum states that scholars now understand the artist was gay. (They also note that few of his letters and personal documents have survived, it being likely he intentionally destroyed ones that would have been incriminating.) In addition to still lifes of flowers, many of his watercolor sketches reveal a life, possibly mixing imagined and real, of underground queerness in the 1910s–20s. Many of these sketches such as Distinguished Air, have a levity and sometimes humor that My Egypt does not radiate. The latter stands strong, though radiant.

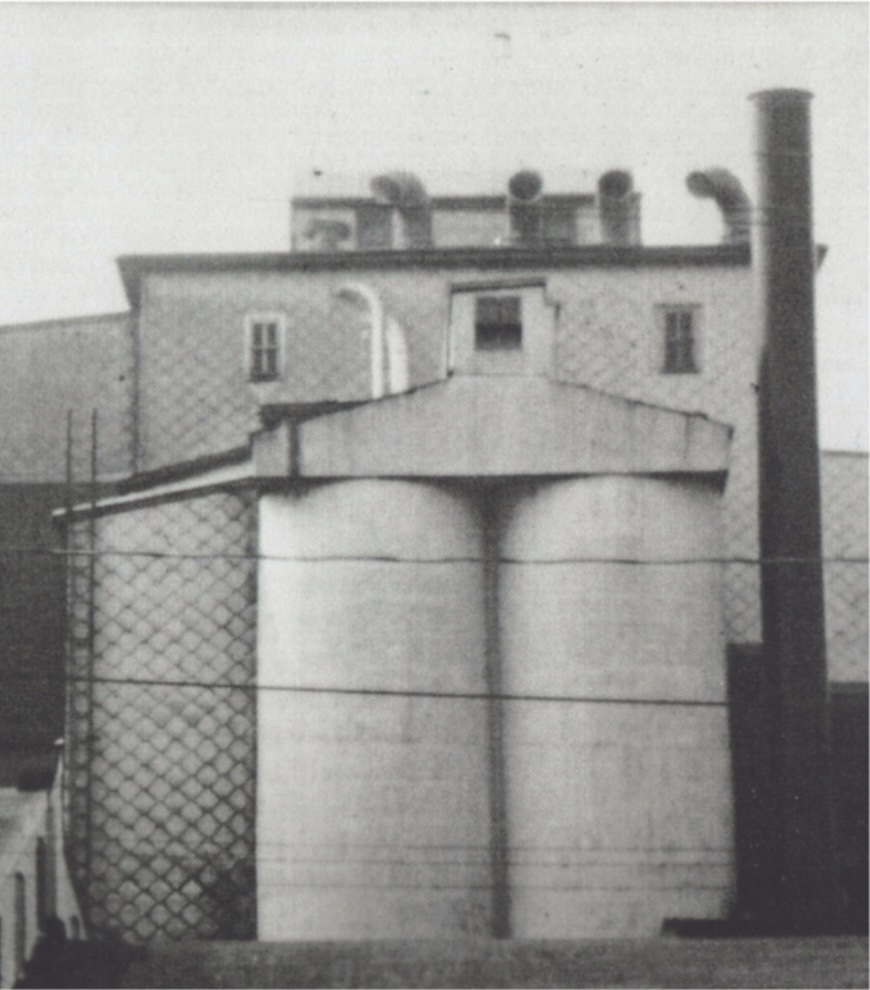

My Egypt confronts the industrial world head-on. The artist “was both attracted and repelled by the modern machine world” (Ritchie 15). At the time, the grain elevator built in 1919 (Marling 33) represented the latest in agricultural technology, in a regional city surrounded by farms with less sophisticated infrastructure. The older brick buildings are visually and metaphorically compressed to the edges of the frame. Notably, the painting does not include any humans: no plant workers, no sidewalk pedestrians. Natural features are minimized as well, with passing inclusions of the ground and sky, the sun represented by a mere fading out of the sky. The supply chain, inputs, outputs are out of frame, the plume of the smokestack reduced to a dissipating wisp. Ritchie assembles Demuth’s compositional sketches, which show the industrial subject and nothing else (85). Though Marling includes a photograph of the Eshelman feed mill in 1919 behind a construction project (34), the 1950 photograph provided by the Demuth Museum shows a perspective on the building near-identical to the painting’s. While the geometry lines up, the photograph, seen through modern eyes, renders a building far less monumental.

The sloped lines and “cool, pristinely modern shapes” (Marley 33) define this work visually. “Ray-like shafts of diagonals” cut across it, in pairs or sets but never in parallel, “forming a kind of net to support the motif of his design” (Ritchie 14). These lines are inspired by the cubism of the era, but never twist or hide. They glorify, emphasize, add structure and extend that of the blocky building itself. Their energy now evokes ever-present shining rays and stage lights in corporate logos and advertising, over this unbranded but intensely corporate monument. The painting’s palette is dominated by grays, blues, and subtle warm tones. In a post-impressionist world, the grays are never simple tones, but richly mixed and textured. Their warmth, along with the shifted geometry of the low vantage point, begin connecting us to the topic in the title.

The title of My Egypt undoubtedly adds layers to our understanding of the painting. Marling connects it to the Great Pyramid of Egypt, the “primordial funerary monument of the Western world,” through the pyramid shape (33). The Egyptian pyramid is an icon by which the entire civilization is remembered. Marling argues Demuth connects his own identity (“My” in the title) as an artist to his rendition of this immortal icon, which we understand as a symbol of the town he later died in. “It was truly, then, his Egypt, a personal emblem of death constructed in terms of the American monument which dominates the skyline of Lancaster.” (While Lancaster today has fared better than many American towns in maintaining a multi-story mixed-use downtown in its now “historic district,” the financial advising chain and supplement store standing on that block today lack any evocation of monuments.)

Jonathan Frederick Walz pushes beyond Marling’s analysis in his 2004 dissertation on the painting. He argues the painter not only attached his identity as an artist to this monumental building, but reached to draw himself corporeally, comparing My Egypt to gallerist Alfred Stieglitz’s portrait of him: both “studies of impenetrable façades” (7). The painting is well-balanced, nearly but never symmetrical, similar to the portrait. He compares the “dandified” cane Demuth walked with to the tall, dark smokestack on the right. Demuth had a disability in his pelvis, as well as diabetes, which left him physically weakened and bed-bound at points in his life (25). Starting in 1922, he underwent a starvation diet for his diabetes, making the bounty of food represented by the grain elevator something to indeed look up at with wonder. Walz notes that “in antiquity Egypt served as the principal source of grain for the Roman Empire,” and his choice of subject evokes Lancaster’s “status as breadbasket” in the Northeastern U.S., one which he painted in other watercolor still lifes (36). While pride exists somewhere in Demuth’s layers of feelings in this painting, he derided his hometown regularly as “the province,” as a well-traveled but forever-inferior-feeling American. Walz connects the invocation of Egypt as “the exotic,” an inside joke of the Dadaist fondness for juxtaposition. The connection of the highlight of this town, with its “plain and simple” local culture, to one of the greatest cultural landmarks ever, emphasizes his own otherness. As a fellow queer Pennsylvanian artist myself, the personal layers Walz peels back hit home.

My Egypt is written about with reverence as a masterpiece of Demuth’s in all three analyses. Ritchie describes the context of the artist’s career in which the work fits. Marling delves deeper into this specific work, bringing together original research and arguments with which to understand the work. More recently, Walz jumps past the simpler narratives of Marling’s to unfurl the personal and cultural threads the painting speaks to. Today, it stands monumentally in the Whitney, hearkening to an era of progress and prosperity a century ago, yet its triangular slashes still point ahead.

Works Cited

The Demuth Museum. “Demuth Museum Text Panels.” The Demuth Museum, https://www.demuth.org/demuth-museum-text-panels.

Marling, Karal Ann. “My Egypt: The Irony of the American Dream.” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 1 (1980): 25–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1180724.

Ritchie, Andrew Carnduff. Charles Demuth. New York City, Museum of Modern Art, 1950, https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_3264_300062075.pdf.

Walz, Jonathan F. The Riddle of the Sphinx Or “it must be Said”: Charles Demuth's “My Egypt” Reconsidered, University of Maryland, College Park, United States—Maryland, 2004. ProQuest, http://proxy.library.nyu.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fdissertations-theses%2Friddle-sphinx-must-be-said-charles-demuths-my%2Fdocview%2F305175121%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D12768.

Unknown Photographer, Eshelman Grain Elevators, c. 1950, Demuth Museum Archives, photo courtesy of S. Lane Faison, Sr.